Serious incidents of violence have forced a change in procedures and equipment. We have put a lot of effort into ensuring that the first police patrol on the scene has the knowledge, skills and equipment to deal with any situation and is, therefore, prepared to stop any dangerous activity or crime against people. National Police Commissioner Seppo Kolehmainen at the police oath ceremony on 23 September 2022.

The following are some stories of survival in dangerous and demanding police tasks in different eras. All of these situations have involved high risks, but the police officers have survived their injuries and been able to continue their work after recovering. Some of the situations are near-misses. The cases are a good illustration of the changes in police practices. Today’s police tactics focus on anticipation, preparedness and obtaining the most accurate background information possible. Yet even today, police officers know they are in for a few scrapes in the line of duty. Something unexpected can always happen that alters the course of events, with fatal consequences.

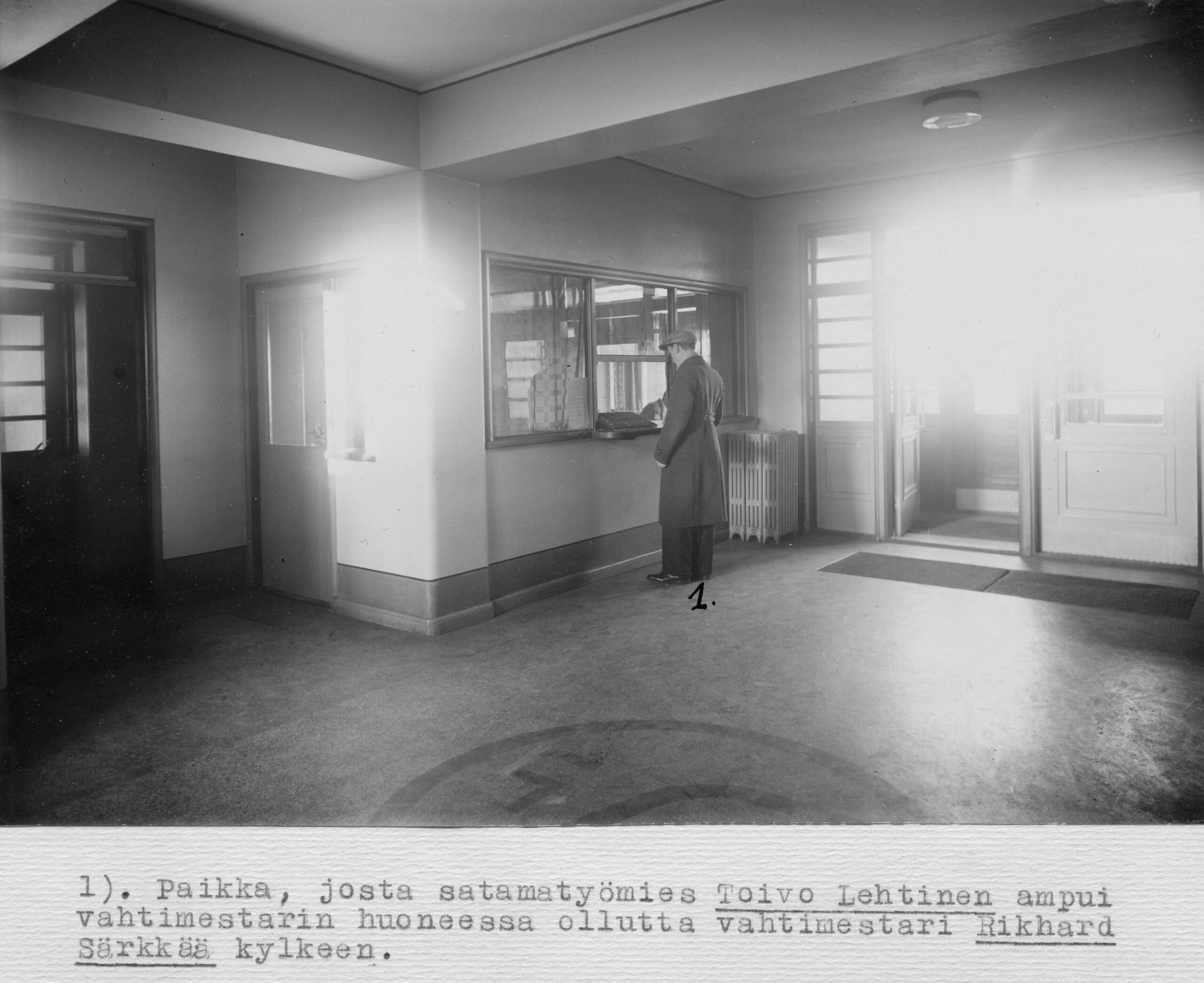

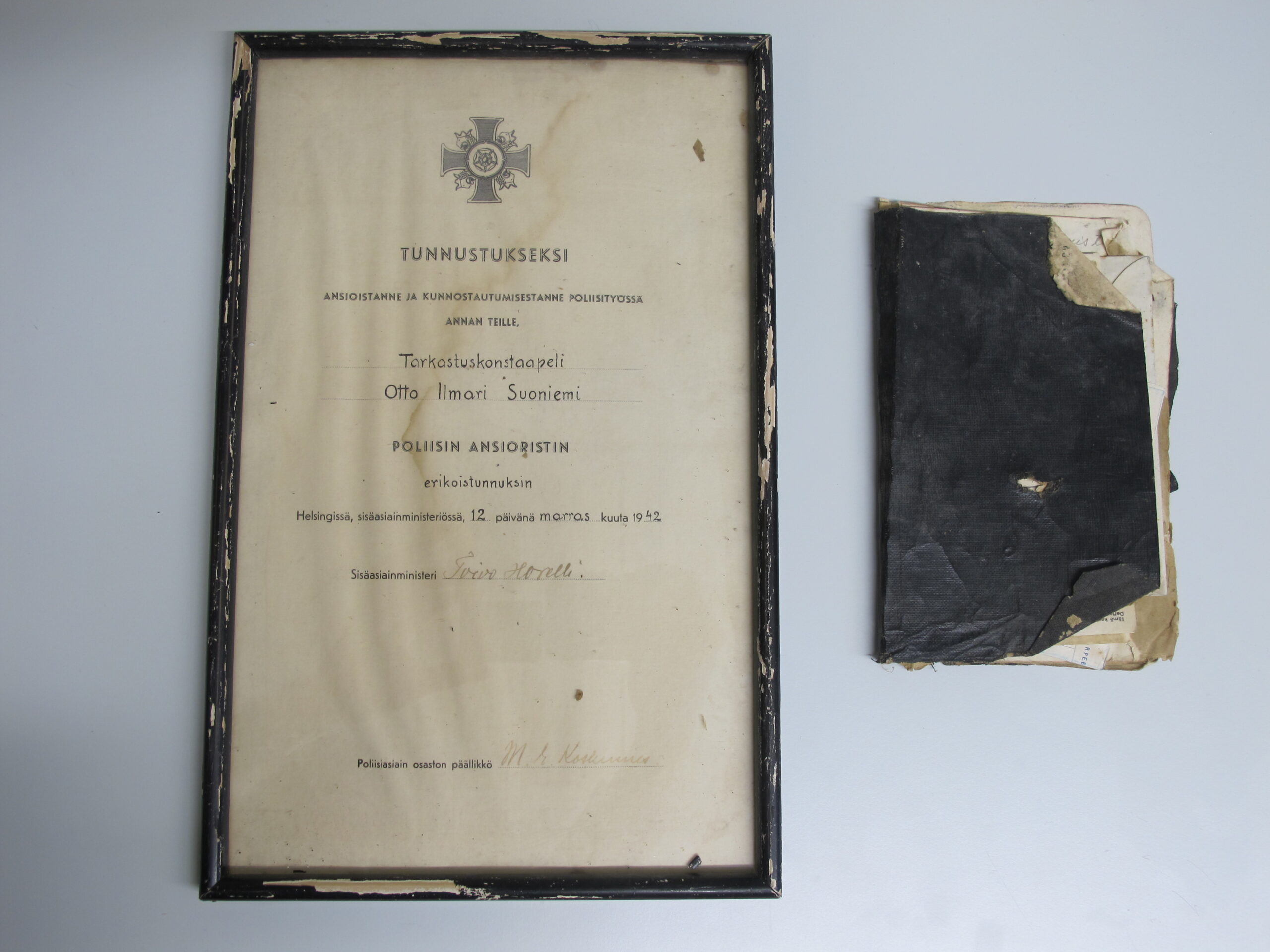

The injury of Detective Sergeant, Patrol Constable Otto Suoniemi in 1942

During the Second World War, the search for objectors occupied the Tampere department of the State Police (Valpo) and the city police. The Communist youth leader was Pellervo Takatalo, a car mechanic. He fought in the Winter War in Summa, but at the outbreak of the Continuation War he began forming a youth resistance group that carried out sabotage. A total of 21 acts of sabotage were carried out in and around Tampere, with explosions destroying army vehicles, railway tracks, trains and transformers. The Ratina power plant and the Tako factory were also hit. Takatalo was arrested but managed to escape in January 1942. In October of the same year, the police were tipped off about his hiding place.

According to a police inquiry, Detective Sergeant Otto Suoniemi of the Tampere Police Department was ordered to head to Lamminpää at 12:30 pm on 31 October 1942 with five police officers from Tampere and two Valpo detectives. The only instruction they received was to take a Suomi submachine gun. Once underway, they were told that they were to arrest the wanted man, Takatalo, who was hiding out in the house. The lady of the house was there, and she knew nothing about Takatalo or his shelter in the basement. Eventually, however, she opened the basement door for the police and promptly fainted. She was carried to bed, and a doctor was called.

The potato box in the basement was found to contain a hatch leading to a staircase to a black door. The police shouted, “Come out or we’ll throw a grenade in.” There was no response. The police fired at the door, and two shots were fired back from the hideout. The police retreated to the sides of the door; Suoniemi, with his submachine gun, moved to a better shooting distance. Soon after, two hand grenades were thrown from the hideout. The room was filled with smoke, it was difficult to breathe and see, and the magazine came out of Suoniemi’s gun. When a third grenade flew out, the submachine gun fell to the floor, Suoniemi was thrown backwards and was hit in the head by shrapnel. From the doorway, a man attacked the detective with Nagant revolvers, shooting Suoniemi in the upper arm. As the men struggled, the detective was shot five times. The detective wrestled the revolvers from the man’s grasp and a knife from his waistband, with which he stabbed him in the upper arm. The man surrendered, and Suoniemi escorted him out. Takatalo had been apprehended.

Both Suoniemi and Takatalo were seriously injured. They were rushed to the critical ward at Hatanpää hospital and placed in the same room. Suoniemi’s wife was afraid that Takatalo would get angry and harm her husband. Suoniemi survived and returned to work in January 1943. The police’s first Crosses of Merit were awarded in November 1942. Suoniemi received it with special commendations. Takatalo later became a detective in the so-called red Valpo.

Apprehending a dangerous individual in Helsinki in the early 1990s

The text is based on real events. The narrator is a young criminal investigator from the Helsinki Police Department who was involved in the incident at the time.

Right from the start, I have to say the following. I’ve never had to shoot at a person in the line of duty. The shooting incidents I’ve been involved with have always required animals to be put down. There have been a few situations where I’ve come close to needing my weapon. The case I’m about to describe didn’t exactly go swimmingly, but we survived it.

My partner and I had been tasked with bringing in a suspect from his apartment in Vuosaari. He already had a criminal record. Now he was suspected of murder. There were three of us detectives, all in plain clothes. The simple idea was to call the caretaker, get him to open the door, go inside, pick the guy up, and bring him in for questioning.

Our colleagues in the robbery division of the bureau of investigation had warned us that the man was dangerous. They described him as completely unpredictable. Based on this, I asked my partner if it would be wise for us to plan a little, think about how we should go in, and maybe get a dog patrol to help. My colleague resisted at first. Of course, the culture back then was totally different. It’s important to understand this. There were no real police tactics, or those that existed were rudimentary. Our leadership structures were very different from today. In practice, patrols on the investigation side worked independently, uniformed officers did their own thing, and there was little cooperation.

Finally, after some deliberation, we decided to call in a field patrol and a caretaker. Our combined experience on the job at that point was probably just under ten years. When the patrol arrived, it boosted our numbers a little: up to perhaps twelve years of experience. In other words, the people on the mission were very young, and, let’s put it this way, rather enthusiastic. Our skills and experience were not exactly fully fledged. One of the guys from the patrol was a course mate, actually, and the other was his more senior colleague. We made a cursory plan: I would open the door, the patrol would enter the apartment first, followed by us detectives as back-up.

The moment arrived. I’ve thought about it a lot. I’m sure I was nervous. The background information was what it was. Perhaps we hadn’t quite grasped that this could be a dangerous mission. We were more like, let’s just go in, grab the guy and bring him in for questioning. 99% of police work is just routine. We got going and did exactly as we’d agreed.

I still remember the apartment. There was a long corridor, with a bedroom at the left end and some kind of living room on the right. Then there was a small corridor with a kitchenette and a toilet on the left. The uniforms went in first. One was holding his baton, but none of them had their guns drawn. We walked inside and looked around. The patrol got to the living room, and we detectives followed side by side. We were at the end of the corridor. The last man was the safety guy. He made sure that the door stayed open in case we needed to make a sharp exit. You can’t imagine the sight that greeted us.

The man was standing almost in the middle of the living room in front of the window, pointing a large automatic pistol at us. It later turned out to be a Colt 1911 semi-automatic pistol. In that moment, the world stopped turning. When you are staring down the barrel of a gun from the business end, it looks pretty damn big. I’ve also wondered whether I had time to be scared or shocked. I’d say no. It was more like stop – what the fuck. In these situations, time slows down. I can’t tell you how long the situation lasted. I can’t remember whether he said anything or not. In any case, my course mate said, as I recall, in a sort of surprised tone, addressing the suspect by his first name: “You’re not going to shoot us, we’re police officers.” He took three steps towards the man, grabbed the gun, and took it out of his hand. Apparently, the surprise was mutual. We told him we were going to handcuff him. When the cuffs clicked closed, the man started to get angry, and shouted expletives at us.

I can’t really define my experience other than to say that it brought everything to a standstill. It made me feel kind of helpless – what was I supposed to do? Of course, I was carrying a gun. I was wondering whether I should go for it. The fact is, if the guy had started shooting, there would probably have been five or more dead and injured police officers in the apartment. In practice, there was nothing you can do when you’re directly in the line of fire at distance of no more than 2, 3 or maybe 4 metres. None of us had bulletproof vests on. You had to buy them yourself. If there were any shared vests at the station, they were the one-size-fits-all kind that you could just throw on. We knew nothing about their age or how effective they were. But we didn’t use them. Instead, we went in there on a wing and a prayer, so to speak. However, I think we did some preparation and planning. Nevertheless, the situation took us by surprise.

We got the suspect into the car and thanked the patrol. I have to admit that yes, we all had fairly sweaty palms. I was a smoker at the time, and we were smoking cigarettes and trying to get our heads around what had happened. I’m the kind of person who feels the reaction almost immediately. After action, I need to have about 15 or 20 minutes to myself before I can talk about anything. The feeling is almost like climbing down from a high place on a rope. It’s both frightening and exhilarating.

Later, I got to know the reactions of my colleagues. I knew the closest guy started to feel it when we got back to the office. He was in a bad mood, argumentative and throwing coffee cups at the wall. One of the others only felt the reaction two days later. Everyone feels something eventually. That goes without saying. People always react to shock sooner or later.

So, perhaps the best way to describe the experience is that it is a complete stop. Time slows down, and you think, ‘What am I going to do now?’ A lot of things happen on autopilot in that situation. Responses arise when you have enough practice in different situations and approaches. Back then, we hadn’t even practised. There was no tactical training, there were no operating models. There was no word of a debriefing. The debriefing was to have a coffee and go and do the next job. Back at the station, I was supposed to question the man we had just brought in. As I recall, it was a difficult interrogation. I couldn’t really get into it. From there, everyone straightened things out for themselves at their own pace, some quickly, others not so quickly. Not much was said about these things. If we talked about them, it was on the sauna benches, and with the help of a few hard drinks.

At that time, I had friends in the Karhu Special Intervention Unit – ones who’d got in there young. They had special expertise. This mission was actually the reason I got interested in firearms and use of force training. I was also into martial arts at the time. I thought that this job should be taken seriously, because there are risks involved, and you have to learn to live with them. It was an education. I don’t know how this has affected the other people involved, but it transformed my attitude to police work. You need to have the skills and knowledge to be able to deal with these situations and not be caught with your pants down. I later worked in the bureau of investigation’s use-of-force training team for many, many years. We dug out Tapani Rinne’s Police Tactics book, which I remember had already been published by then, and we studied all sorts of techniques and tactics, and of course practiced them. It was kind of self-directed. At some point, the head of the department gave me proper authorisation to continue the training, and I was allowed to use my working time for that. It was a smart decision. Police professionalism has many elements: use of force, tactics, legislation, communication, both written and spoken. These make up the professionalism of the police. And at that time, of course, you had to get everyone, including the brass, to understand the importance of training and preparation. Attitudes in the 1990s were very different from today.

A helmet saved the life of a police officer in Oulu

In Oulu, at about 6 pm on Wednesday 13 January 2015, a man entered a pub with an axe, killed two men, wounded a third and left. The person who called the emergency response centre identified the man and knew where he lived. The police were quickly on the tail of the suspect.

The police launched an operation involving several dozen patrols. The man was located, and the Oulu Police Department’s special unit, known as Oulun Valo, went to an apartment to apprehend him. At the location, after getting the door open, an officer from the special unit ordered anyone who was in the dark apartment to come out with their hands visible. According to the pre-trial investigation, it was obvious that the person who issued this order was a police officer and that the police officer was prepared to use a weapon in the situation.

The suspect was hiding next to the front door, pressed against the wall. He threw a hammer, which flew over the special unit and into the stairwell. Then, with the axe raised in a striking position, he attacked the first police officer in the special unit. The officer was about a metre away, and the axe struck him in the helmet. The police officer who was hit shot the attacker in the torso. At the same time, the suspect raised his axe to strike again, and the policeman fired another shot, also into the suspect’s torso. The suspect fell to the floor as a result of the shot. First aid was administered immediately, but he died of his injuries.

The police officer sustained only minor injuries. The special unit had recently received the new helmets. It was that helmet and its thick visor that saved his life, as it was more shock-resistant than the old one. No pre-trial investigation was opened because the head investigator, the district prosecutor, considered the police action to be aligned with the guidelines and self-defence. The police officer returned to work.

The Police Museum’s collection includes the helmet that saved the officer’s life: there is a cut in the protective fabric and an impact mark on the visor.

Motorcycle police officer injured in a chase in Ylitornio

In September 2016, a police patrol on traffic surveillance duty in Ylitornio tried to stop a cross-country ATV that was driving illegally on a highway. The driver of the ATV disobeyed the police’s signs to stop and continued to drive recklessly.

A police officer on a motorbike pulled alongside the ATV with the intention of ordering the driver to stop when the driver swerved in front of the motorbike, crossing a lane of oncoming traffic, and went over the left edge of the road. The motorcycle police officer ran into a guardrail on the side of the road and flew into the road. The driver of the ATV fled the scene. The police officer was seriously injured.

The District Court found the driver guilty of attempted murder, violent resistance to a public official, causing a serious traffic hazard, and unauthorised operating of a vehicle, but the Rovaniemi Court of Appeal considered the act to be attempted homicide. The man’s nine-and-a-half-year prison sentence was reduced to six years. The Court of Appeal ruled that the man’s intention was to escape, not to kill the police officer.

A man shot at police officers in Lempäälä

In spring 2018, the police stopped a passenger car in Lempäälä. The car fled, and the police started to follow it. There were three people in the car. The two young men who were passengers got out of the car at the first stop, but the driver continued to flee alone. During the chase, the vehicle reached speeds of up to 180 kilometres per hour. After chasing the car for several kilometres, the police stopped it by driving in front of it to block it off.

Several police patrols were involved in the chase, and three were around the car when it was stopped. The patrols tried to persuade the driver to surrender by first ordering him to do so and eventually threatening him with their weapons. The man responded by firing a homemade shotgun through the windscreen of the car at the police officers. Two police officers returned fire, killing the man. One police officer was injured in the shooting.

According to the investigation, no other persons were involved in the crime, and the man was alone in the car when he shot at the police. He was suspected of attempted murder and assaulting an officer, as well as an aggravated firearms offence and six traffic offences relating to his driving and the condition of the vehicle. The prosecutor/head investigator decided that there was no reason to open a pre-trial investigation into the actions of the police and that the police officers had acted in self-defence. The prosecutor found that the police acted appropriately and that there is no reason to suspect a crime.

Two police officers injured in an ambush in Porvoo in 2019

I had the feeling I was going to die in this situation. Pre-trial investigation record, testimony of a senior constable.

On 25 August 2019, an officer of the Eastern Uusimaa police was ambushed in Porvoo. The perpetrators were brothers with a Finnish background who had travelled to Finland from Sweden with the intention of acquiring more weapons. On the evening of Saturday 24 August 2019, they called the emergency response centre and claimed that a brawl was underway in a sand quarry in Piirlahti, Porvoo. According to the police, and later also the prosecutor, the men’s intention was to lure a police patrol to the scene and rob them of their guns, ammunition and other police equipment. However, a patrol from the Eastern Uusimaa Police Department did not encounter the brothers.

On the night of Sunday 25 August, the men tried again. One of them made an emergency call claiming that someone had tried to break into his car in the Ölsten industrial area of Porvoo. Another patrol from the Eastern Uusimaa Police Department was assigned the task as a non-urgent category B task.

The police patrol arrived at the scene and was surprised to see two armed men. One of the officers, a senior constable, got out of the car and went over to the men. The sergeant, who remained in the vehicle, watched as the men immediately incapacitated his partner. One of the men had a gun, and he pointed it at the police officer’s head and pulled him in front of him for protection. The man occasionally pointed at the police officer in the patrol car. The sergeant drew his gun but could not fire because his partner was being used as a human shield. The officer who had been taken hostage heard one of them say in Finnish “I’ll kill you”. The men demanded the police officers’ uniforms.

The sergeant backed away with his weapon raised, ordering the suspect as follows: “Police, drop the gun or I’ll shoot.” The men, in turn, shouted at the sergeant to hand over his gun. The sergeant shouted that he would not do that. The men threatened to kill their hostage. They emphasised their threat by pressing the gun to the officer’s neck and then his temple. The sergeant backed away slowly and pressed the emergency button on his Virve phone. At the same time, he shouted into the radio that his partner had been taken hostage. That is when the sergeant heard a shot, followed shortly after by another shot. A bullet hit the sergeant in the arm. The brothers fired a third shot, but it missed. The wounded sergeant backed away and took cover.

The constable who had been taken hostage had momentarily lost his hearing because the shots had been fired right next to his ear. One of the men took the officer’s service weapon from the holster and cocked it. The men began demanding that the officer hand over the patrol’s support weapon. The officer said that the gun was in a locked box and he did not have the key. One of the men started to search the police car. The man who was holding the police officer hostage lowered the hand with the gun in it for a moment. That is when the constable ran away. After a few steps, the constable heard gunshots and felt that he had been hit in the side and back. He fell forward into the street but immediately got up and continued running. More shots were fired, but they missed. The officer did not know how badly he was wounded, so he decided to run for as long as he could. He feared he might soon fall for the last time. A short distance away, the sergeant heard the gunshots and became concerned about his partner’s situation. He decided to approach the car again. Just then he heard his partner shouting on the radio that he had been wounded but had escaped.

At the police car, the brothers loaded their guns, took the constable’s service weapon with them, and took heavy protective vests from the police car. They then fled before reinforcements had time to arrive. The sergeant’s arm was seriously injured by the bullet. The senior constable’s protective vest had stopped the bullets that had hit him.

The police quickly caught up with the shooters and followed them to Tampere. In the early evening, the police caught up with the men’s car and tried to prevent it from entering the lakeshore tunnel in Tampere. This was unsuccessful, and the men fired several shots at the police while continuing to flee. They were finally apprehended in Ikaalinen following a 30-minute pursuit.

The District Court of Eastern Uusimaa sentenced both men to 15 years in prison for attempted murder and numerous other offences.