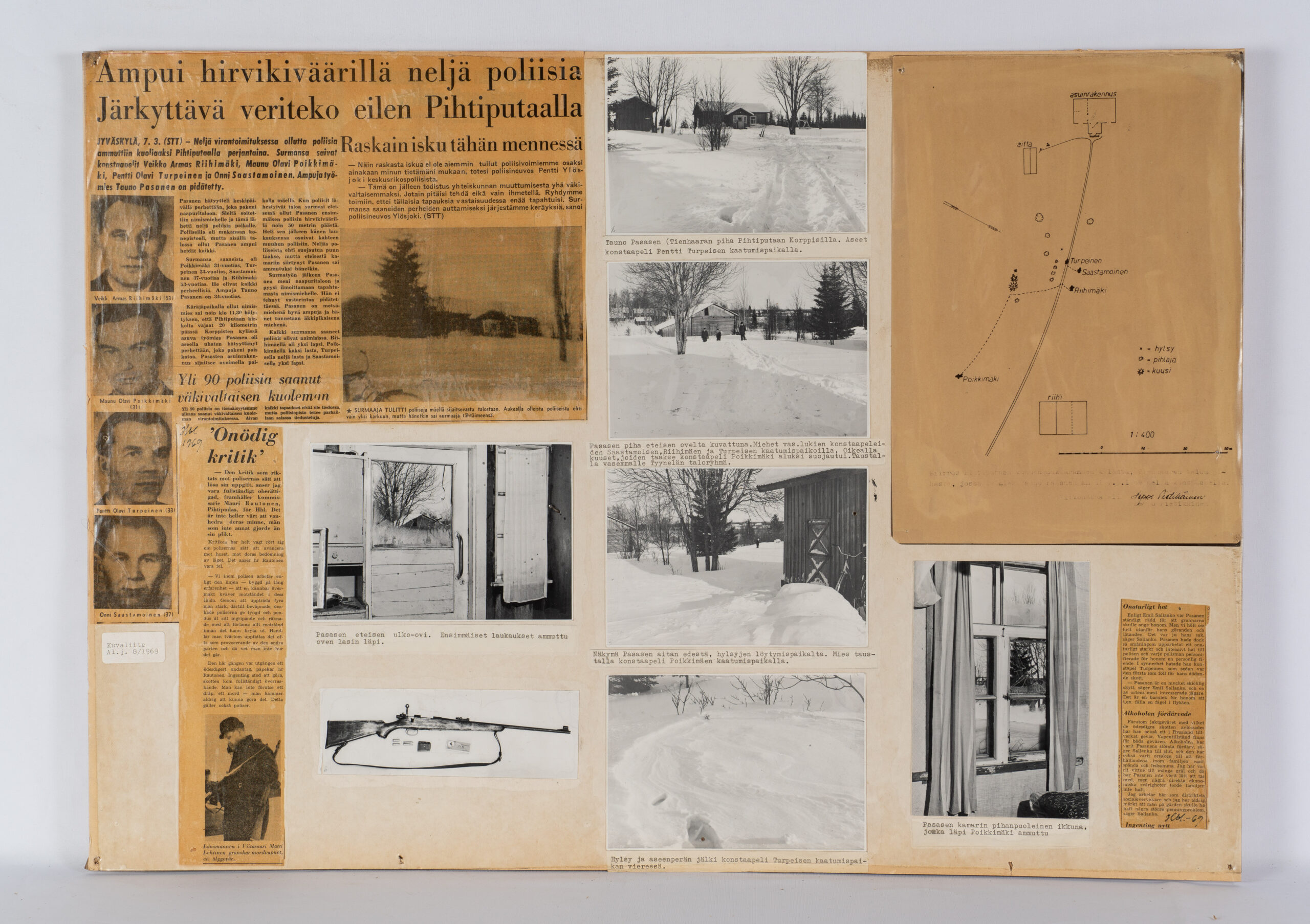

In 1969, a 33-year-old farmer in Pihtipudas killed four police officers who had come to arrest him following a report. Preliminary information received by the police indicated that the perpetrator had already fired shots at home, so the police officers were equipped with a Suomi sub-machine gun in addition to their service weapons. The killings were uniquely tragic in the history of the Finnish police: never before have so many police officers died in the line of duty at once. In today’s terms, we would be talking about mass murder.

Eight Deadly Bullets, a TV series and film

The four-part TV film “Eight Deadly Bullets”, written and directed by Mikko Niskanen, was shown on television in 1972. The TV series was also made into a shortened feature film of the same name. In Niskanen’s film, the role of the police was central, although not the main role. The film is partly based on true events.

Niskanen’s film was made just three years after the police killings. The film must be viewed in the political-cultural context of its time. Social debate intensified in the late 1960s, and television was criticised. Foreign series in particular were criticised for being violent and unrealistic. Yle’s informative programme policy of 1966 defined television’s mission as “providing a world view based on correct information and facts”. It was to stir debate, and different, even radical opinions should be expressed.

I knew immediately that the shots in Pihtipudas marked the end of a long and consistent chain of events. I realised that there was a whole range of problems in the background, Niskanen said of his film. The film was well received, winning Jussi awards for Best Director and Best Actor. Niskanen was also awarded the 1972 State Film Artist Prize. The TV drama emphasised the importance of circumstances, and the protagonist was seen as a “victim” of them. The issues in the frame were rural unemployment, marginalisation, and the gap between decision-makers and ordinary people. The police, who implemented the decisions of those in power, were the surrogate victims of the drama.

Artistic merit

The artistic merits of Niskanen’s film are undeniable. Film critics chose it as one of the ten best Finnish films in a 2012 survey conducted by Yle News. The film was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in October 2013. The New York Times published an in-depth review of the film, calling it brilliant. The review even boldly suggested that Niskanen’s film was a model for the crime series “The Wire”, “Breaking Bad” and “The Killing”. All these productions look at crime from different perspectives. The possible causes of the events are also examined from the perspective of the perpetrator.

What really happened in Pihtipudas?

The pre-trial investigation material of the Pihtipudas police murders paints a different picture of events than the film. In a scene lasting about ten minutes, the killing of the policemen is described as the act of a tired, anguished and panicked man, with the shot from a distance. When the man sees the police approaching the house, he fires the first four shots from inside the house and the next two from the yard. The final two shots are only heard but not seen. Only after the first shots are fired are some of the victims shown falling to the ground and others trying to crawl to cover. Finally, from a distance, a man is shown putting a gun in a snowdrift next to one of the victims and walking down the path to the neighbouring house. According to the pre-trial investigation material, the details of the act are inconsistent with a panicked or anguished perpetrator.

The film does not show the cruellest parts of the act. Four police officers walked down a snowy path, one after the other, towards the house. The man opened fire with a Sako hunting rifle (7×33 calibre) from the window of the hallway when the police were about 50 metres away. Two of the policemen fell on the path, a third fell to the left of the path, and the fourth ran for cover behind a fir tree. The man continued shooting. He eventually went outside and fatally shot one officer who was lying on the ground and another who was trying to escape, execution style, at close range while the victims were still alive. After the killings, the man placed his gun facing up next to the first person he had killed. Based on the empty cartridges found, at least ten shots were fired. Why did the perpetrator not stop this bloodthirsty act? Why did he continue until all the police officers were surely dead? In its incomprehensibility, this question remains a perpetual mystery.

Conviction and pardoning

The shooter was sentenced to life imprisonment in a penitentiary for the premeditated homicide of four people. He was released in 1982; pardoned by President Mauno Koivisto, having served about 12 years in prison. In 1996, the man committed another homicide, killing his ex-wife. He was convicted as a first-time offender because it had been so long since his life sentence. At the time, the pardoning of the convict caused quite some debate. The fictional portrayal of the perpetrator as a victim of society was considered to have had too much influence on the decision to release him.

Niskanen had probably read the police’s pre-trial investigation material. Of course, an artist should have artistic freedom, and Niskanen’s film is a shining example of the power and influence of fiction. Fiction can easily be used to emphasise a desired perspective or to obscure facts that are relevant to reality. The responsibility of fiction should also be discussed when dealing with real-life events, as a work of fiction can easily become the “official” truth among the general public. The truth should not be arbitrarily altered on the basis of artistic freedom alone.

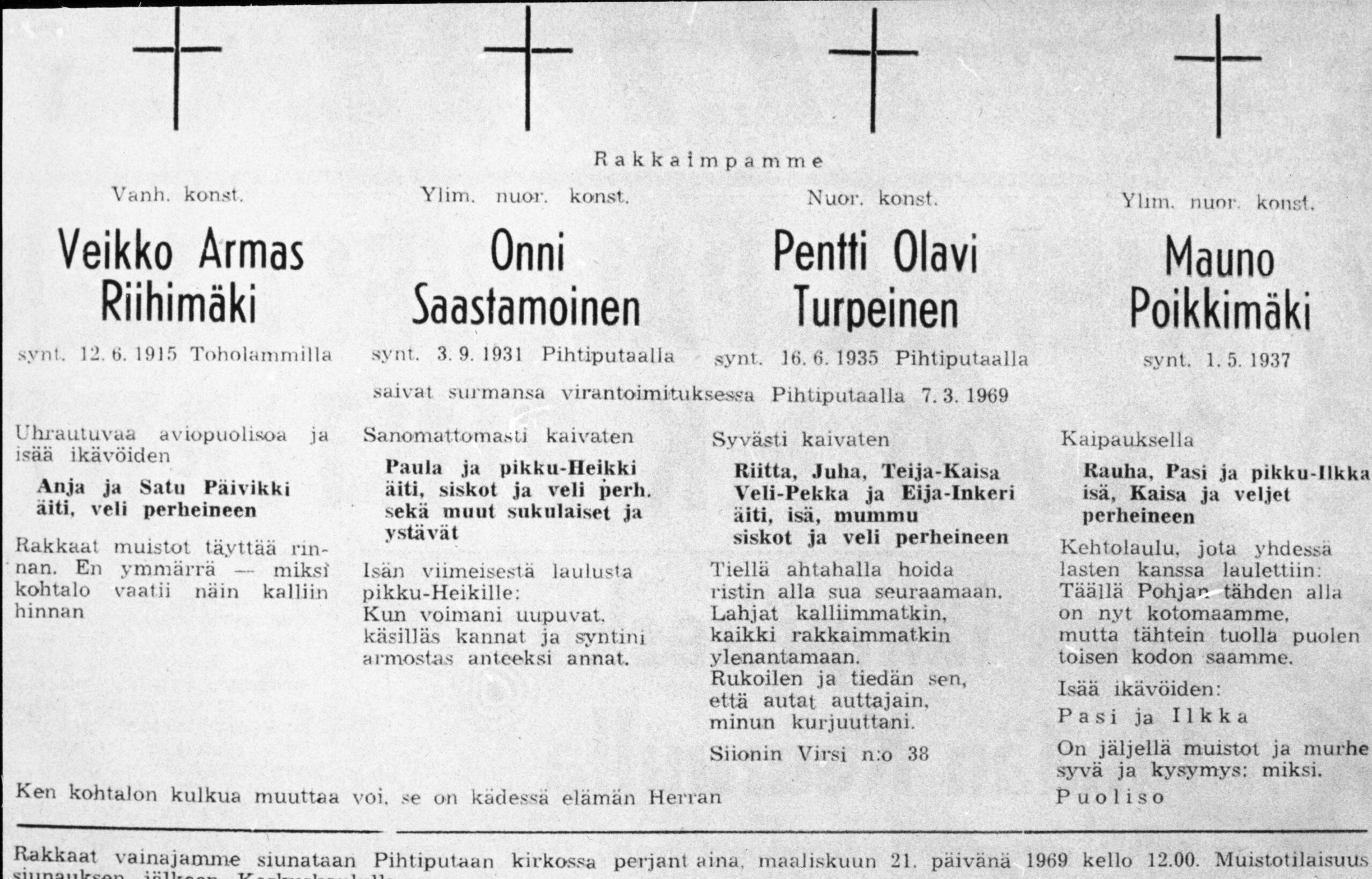

In real life, the victims of homicides are always the people who die, the relatives of the victims and of the perpetrator, and the surrounding community. For example, Veikko Riihimäki (53), who died in the Pihtipudas killings, was survived by his wife and one child, Onni Saastamoinen (38) had a wife and a 3-month-old baby, Pentti Turpeinen (33) had a wife and four children, and Mauno Poikkimäki (31) was survived by his wife and two children.

The Pihtipudas police murders cast long shadows

Heikki Saastamoinen, the son of Constable Onni Saastamoinen, was a three-month-old baby when his father was killed. In an interview with the Police Museum, he recalled how the death of his father had affected his and his mother’s life. Although he has no memories of his father, the events in Pihtipudas have had decades of impact.

Growing up without a father

I was my parents’ firstborn. My father was 38 and my mother was 27 when I was born. As a child, I remember having dreams that my father came back and we met at the house. I was a child longing for a father, but that feeling has gone now.

As I’ve got older, I’ve realised that not having a father has affected me. My mother never remarried. I grew up without seeing what a father or a husband should be. Sometimes, I would have like to have asked my father for advice. This may have been a factor in my own divorces. Perhaps I would have been a better father and husband if I’d had a father to set an example for me.

Of course, I don’t remember experiencing the loss of my father. I’m sure my father sometimes held me in his arms or tucked me in. It would have been even worse if this had happened to an older child who’d lived with their father, for example. I grew up with my father always being away.

My father’s death was a shocking act that cannot be explained, but I found a reason for it. My father died because he defended law and order, sacrificed himself for this country. That’s a much better reason for the father to be away than for him to have got drunk and crashed his car into a telephone pole. My father died a hero. For an older person, the loss would have been much more traumatic, lifelong and even transgenerational.

Dealing with sorrow in the family

I haven’t been told much about the events themselves. I may never know what really happened. I’ve heard the speeches and read the newspaper articles. I’ve formed my understanding of it through these.

My mother was always a victim, and she never really got over what happened in her life. There was no crisis assistance back in 1969. There might not even have been enough help for four families in a small town. She felt like she was left to deal with it alone and should have received more support. This made her bitter, although she also had a strong spirit and a fierce will to survive. Perhaps initially there had been doubts about how she would cope with a child on her own. That’s why she thought she had to show she could manage. In addition, she was new to the area and did not know the people. It was different for the other families – they had been in the area for a long time.

I don’t know if the other widows had similar experiences. Maybe they kept in touch with each other to begin with, I don’t know. At least later on, we had nothing to do with them. I met Riitta Turpeinen once at a scout camp more than 40 years ago. She was a cook, and I was an instructor. Yes, there was an unusual kind of connection. This tragedy united us.

I think other relationships were broken as well. My mother couldn’t see that she wasn’t the only one who lost something. She had only known my father a short while, but his family had known him for decades. She didn’t take the loss of others very seriously, and it led to conflict. We had little contact with my father’s family, even though we went to live on the farm where he grew up. She didn’t want to accept help or advice on how to do things. So helping us didn’t really come to anything. It always needed to be on my mother’s terms.

My mother got a widow’s pension and that was our livelihood. She didn’t go to work until I was about 12 years old. We had no cattle, even though the barn had been renovated. My paternal grandmother said that everything would be ruined if they were empty: “At least take some sheep”. So we got some sheep. I don’t think they made any economic sense; we had to make hay, and we didn’t have a tractor or a horse. Perhaps it was therapeutic for my mother. It was something to keep her busy day-to-day.

The house no longer exists – it’s been sold. I’ve visited my father’s grave occasionally. There is one peculiar thing. The coffins are in a different order to the names on the stone. My mother and I picked some lilacs from our garden to take to the grave. I remember that my mother put the flowers in the place where the coffin was, not my father’s name. I don’t know how that happened. When a memorial was erected for the victims, my mother didn’t want us to attend.

A police officer’s son at school

I was taken aback when the other kids at school started talking about it. Am I really famous for what had happened to my father? I was also bullied at school. Not everyone in Pihtipudas loved the police, after all. Some of the bullies and their families had more sympathy for Pasanen.

Being the son of a policeman and having no one to defend me, no father or brothers to come to my aid, made me an easy target for the bullies. I have to wonder how I got through it without major trauma. Maybe it left me with a certain mistrust of people and the idea of whether I belonged in the group or not.

There was school violence in those days too. Often on Fridays, I would get beaten up waiting for school taxis. These were not the highlights of my life. In a way, my bullies must have been annoyed because I was good at school. It was important and precious to me to be the son of a policeman. I guess that’s why I thought that in school you have to be honest, do your homework and answer questions.

When I tried to tell my mother about this, she didn’t believe me. It was a terrible situation when you couldn’t get help. I just have to wonder how God let me survive and I didn’t give up or go off the rails. There was no choice but to survive and move on, to believe in the future. Fortunately, the bullying stopped in secondary school.

Memory of the father

I still have my father’s police photograph on the wall of my house. I remember when I was student, when times were hard, I wore my dad’s blue uniform and a long jacket that no longer had police insignia on it. I’ve also saved the newspaper articles.

I’ve told my children why I don’t have a grandfather. Grandma lives on her own because grandpa is dead. He was a policeman who was shot by a man. I’m sure we had a chat about it, and I got the impression that it scared the children. Oh, so that can happen? Even though the police are supposed to protect us? Are the police not safe themselves?

My own mother was three weeks old when her father was killed in the war. Actually, I was lucky, I was already three months old when my father died. We have one family photo, all of us together, me on my father’s lap. My mother never saw her father, was never held in his arms. Perhaps this is how my mother ended up feeling like a victim in life.

The Pihtipudas murders are remembered

Once, on an aeroplane, I was chatting to the person next to me about families, especially our fathers. I said I didn’t have much experience of the subject, because my father died in the Pihtipudas killings. He offered his condolences and said he remembered the events very well.

There have also been unpleasant encounters. In the mid-1990s, a person recognised me on a train and came up to me and said “Yes, Pasanen did the right thing, every policeman should be killed”. It was hard to swallow. When a drunk man thinks so, I thought it better to change seats than to stay there and argue with him. I didn’t recognise the person in any way. Another time, someone told me to my face “Oh, it’s you. The right thing happened to your father.”

The impact of Mikko Niskanen’s Eight Deadly Bullets

Niskanen was well known in Pihtipudas. But they weren’t talking about his film. Instead, people thought that Niskanen was no longer welcome in the area. They should have hung him from the flagpole by the store for making that film. I don’t know what his motive was.

I wasn’t involved in these discussions and haven’t watched Niskanen’s productions. I understand that he tried to portray the plight of the small farmer and succeeded in doing so. He probably would have made a pretty good series if he hadn’t involved the police killings in it. In my view, the depiction of all the misery even sought to justify that act. Niskanen, a leftist, wanted to highlight misery and poverty. I don’t want to look into it any further. I think the film was made to sell tragedy at the expense of the victims. The course of events was made to look different and does not do justice to the victims or their families.

The perpetrator was pardoned for his offence. Even if he hadn’t been pardoned, he served his time. From my point of view, it really doesn’t matter how long his sentence was. It wouldn’t have brought my father back. Still, it was inconceivable that the perpetrator was pardoned after only 12 years. Because of this, I don’t have much respect for President Koivisto. My mother and I didn’t talk about this. I know something about the later stages of the perpetrator’s life. Things didn’t go well for him. I’m sure someone felt they had more in common with him than with the police. There is always someone who indirectly feels justified in killing those in authority. Of course, it makes a difference if you are on the other side of the law. Personally, I haven’t ended up on the wrong side of the law, and I’m sure my father’s legacy has influenced that.

One Saastamoinen has already been gunned down. I won’t let it happen again.

In the early 2000s, I found myself in a situation where my wife and I were held at gunpoint. My wife said we should run for the forest path. I said, “One Saastamoinen has already been gunned down. I won’t let it happen again.” For me it was a very spontaneous reaction. I saw the person with the gun wavering, and I decided to act; I prised the gun from his hands. There was no time to think; I had to act and I succeeded. The police came to pick up the man.