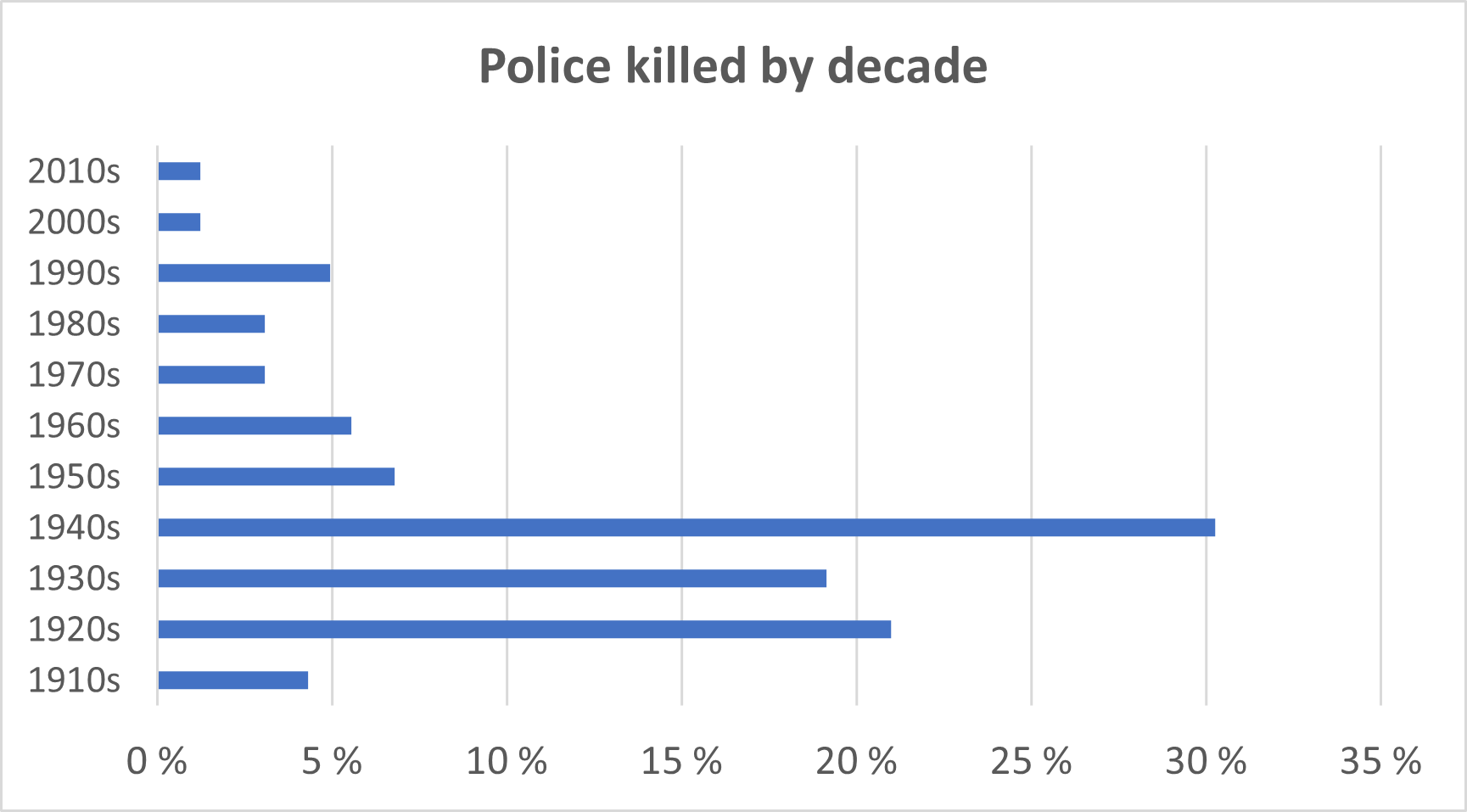

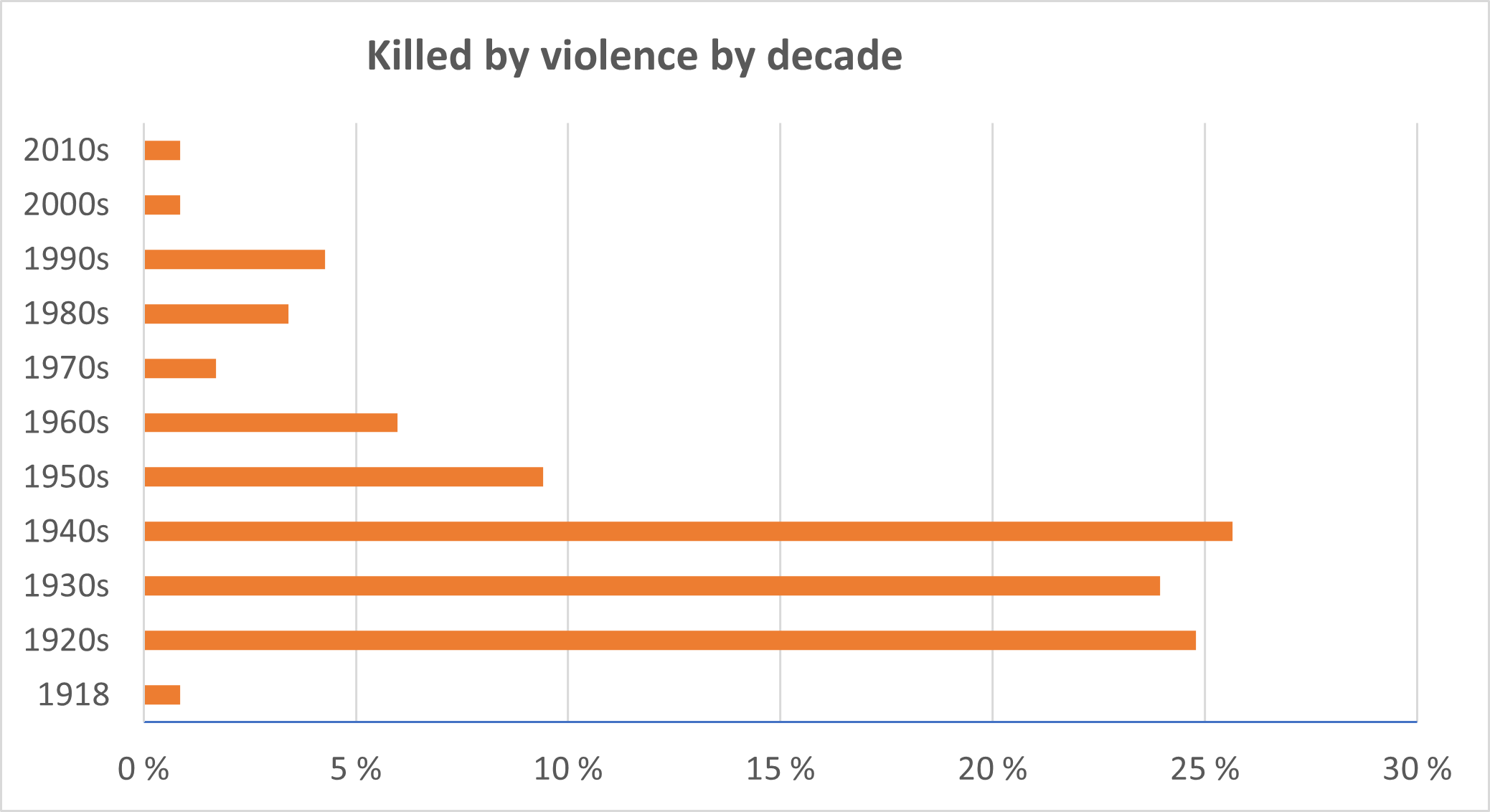

The first three decades of Finland’s independence were the most dangerous time to be a police officer. Almost 73% of police fatalities occurred between 1918 and 1949. The 2000s appear to be the safest period, showing that the police have invested heavily in training and safety at work. The last time a police officer was killed in the line of duty was in 2016 in Vihti.

Notes on terms and data

A police fatality is the death of a police officer that happens in the line of duty or is materially connected to the official duties of the police. Such fatalities often occur in violent or life-threatening situations. A police fatality is always an extraordinary tragedy, both for the police community and for society as a whole.

Diagram: Police fatalities by decade

The available data do not give an overall picture of the number of police officers killed during the Civil War and the Second World War. Separate articles on these periods will be published later in the online exhibition.

The proportion of fatalities occurring during the Civil War appears too low. During the three and a half months of the Civil War, there was terror from both the Reds and Whites. According to the database of war deaths from 1914 to 1922 at the National Archive, 72 people whose job title referred to the police died in the Civil War. Of these, 68% were Whites, 25% were Reds, and the remaining 7% were unknown.

We can also consider whether the execution of a police officer in the Civil War was a police fatality or a war death. A police officer acting impartially could be the target of terror from the other side simply for doing their official duty. Not all officials who were killed, whether Red or White, had chosen their side. However, the environment interpreted them as belonging to one specific camp. Those who endeavoured to uphold law, order and security regardless of social divisions had it the hardest.

In Memoriam 1917–2007 features six police fatalities from the Civil War: two police officers and an attendant at a police station were executed by the Reds, two police officers were killed in an ambush by the Reds, and one police officer was killed in combat while fighting for the Whites. The last of these was no longer a police officer on the date of death. The first actual peacetime death occurred in October 1918, when a Constable Yrjö Huhtamäki was shot dead in Ilmajoki while investigating a hay theft.

Despite the turbulent state of society in 1919, fears of further unrest, and the entry into force of Prohibition, no police officer is known to have been killed in the line of duty that year. This information may be uncertain. The earliest regular information on police fatalities was collected from journals published later on. Suomen Poliisilehti first came out in 1921 and Poliisimies only in 1929. For this reason, the information for 1919 is sourced from other newspaper material.

In general, information about the oldest fatalities is patchy. Some information can be found in the archives of police families, and some may be passed down through the generations. Unfortunately, some cases may also have been forgotten over time. There are no guarantees that every fatality was eventually reported in the obituaries of journals. Information from genealogists and historians is extremely valuable. It is easier to start mapping events when you have a name to go by.

Causes and motives of the killings

While the Prohibition Act was in force, Finland experienced an extraordinary wave of violent crime, which Mikko Porvali describes in a section of the online exhibition titled The Dangerous Prohibition Years. As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s, Finland was marked by an exceptionally high homicide rate, reaching almost 100 victims per 100,000 inhabitants per year. The police force also paid a price for this. Police officers were often killed while trying to settle a drunken brawl or calm a disorderly person. In addition, raids on alcohol smugglers occasionally ended in tragedy for the police.

In the early years of Finland’s independence, police training was brief, lasting only a few weeks, and emphasised physical training. Shooting exercises taught officers the essentials. Many constables started under the guidance of a more experienced colleague before moving on to the actual training. Training on shooting skills in practical work was apparently inconsistent. It depended on the officer’s own interest and the demands of their job. Perhaps some of the earlier deaths could have been prevented if the police had received more in-depth training and guidance on how to anticipate situations and identify potential threats.

The element of surprise was a key characteristic of the police fatalities from the 1920s to the 1940s: for example, a suspect may suddenly draw a bladed weapon or firearm while they were being transported. This begs the question of how police officers were trained to search people and find dangerous objects in the early years of Finland’s independence. The perpetrators were often locals, and crimes were committed in familiar territory, so most likely the police knew the person they were arresting or taking in for questioning. It may be that the police were not always as vigilant as they should have been when searching an “old acquaintance”. There are several examples of a police officer stepping through a doorway and being shot immediately, or a person talking calmly with a police officer but then deciding to kill the officer.

It is understandable that a few weeks of training cannot provide more than a superficial overview of the profession, and officers learnt on the job. In 2025, it takes three years to complete a bachelor’s degree in policing. Nonetheless, a fresh graduate is not all-knowing, despite receiving more in-depth training than previous generations of police officers. However, they are better prepared – there is no doubt about that.

Some of those killed were at the very beginning of their careers, while others were on the verge of retirement. Therefore, it is impossible to conclude that younger police officers were more likely to become victims than more experienced ones. The police tactics of force and firmness also had an impact.

During the “danger years” of police fatalities, it was common for a police officer to work alone, go to a person’s home to bring them in, and end up being killed. At least in small towns, the constable knew almost every house and every person in the community. Locals also knew him and knew where he lived. This carried its own risks, which led to a great tragedy in 1931 in Lamminkylä, North Pirkkala, when a police officer’s wife was killed when drunken men broke into their home. Sergeant Anton Lundqvist, who later arrived to arrest the men, was also shot.

The legacy of the Civil War was reflected in attitudes towards the police. The losing side generally had little sympathy for police officers recruited from the ranks of the winners, and this may also have been a factor in the killings. Sometimes, the killings were politically motivated. In Heinola in 1930, Senior Constable Ivar Kokkonen went to arrest a known communist who fatally shot Kokkonen in the yard of his house. The person fled to the Soviet Union.

Soldiers also killed police officers. A jaeger lieutenant shot and killed Sergeant Juho Järvi at Vaasa police station in 1921. The shooter was so drunk that, in his own words, he thought he was fighting the Bolsheviks. He was held to be criminally unaccountable for the death. In 1930, Senior Detective Karl Jäspi was killed while keeping an eye on the barracks in Pori with a colleague. The area was suspected of harbouring communists with criminal intentions. Near the barracks, the officers encountered two men in civilian clothing and engaged them in conversation. The situation led to a scuffle as officers tried to arrest the men. One of them fired a shot that hit Jäspi. The men turned out to be non-commissioned officers of the Pori regiment, who were on the move for the same reason as the police. They were not convicted.

It is estimated that around 170 police officers died in Finland during the war years from 1939 to 1944. Fifty of them were killed in police action on the home front, and around 120 were killed in the line of duty in the armed forces. In addition to regular police duties, police officers were killed in civil defence work when residential areas were bombed, when capturing paratroopers and deserters, and by being killed by prisoners of war. In February 1940 alone, a total of ten policemen were killed in bombings.

The most dangerous years to be a police officer were 1958 and 1969: four officers died in both of those years. The fatalities in 1958 arose during arrests and robberies. Four policemen were killed in Pihtipudas in 1969 when they went to calm a man who was rampaging at home with a gun.

The number of police fatalities decreased in the 1970s and 1980s but went back up in the 1990s. Looking at the period as a whole, the number of killings in the 1990s was not exceptional, but the police fatalities in Helsinki in 1997 represent a distinct spike in the statistics. The decline in police fatalities was certainly due to longer training periods and, as a result, better professional skills. The Police Act also obliged the police to use less force wherever possible. In the 1990s, education in the use of force and tactics began to pay off, and in the 21st century, police killings have fortunately been rare. The urbanisation of society reduced the need for firearms. However, Finland has a large number of hunters and gun enthusiasts. According to the Ministry of the Interior, about 460,000 people have a gun licence, and there are just under 1.5 million licensed weapons in Finland. Gun laws have become significantly stricter in the 21st century.

A less common but clearly distinctive cause of police deaths is traffic: hit-and-runs, collisions and road accidents. In 1926, Constable Lauri Santala was hit by a car when a motorist swerved to avoid another car on Hämeenkatu in Tampere. The streetlights were out at the time. An accident involving a police officer had already occurred earlier in somewhat embarrassing circumstances. Police officers in the Malmi district had confiscated a car from some alcohol smugglers and taken it to the yard of the police station. The officer on duty decided to go for a drive, even though this was strictly forbidden. He also picked up three other people. The driver lost control of the car and crashed into a house. The officer died from his injuries in hospital.

A recurring pattern in traffic-related police fatalities has been a hit-and-run driver failing to obey a police order to stop and crashing into a police officer. In traffic stops, there is little a police officer standing in the road can do about a speeding vehicle. It should also be noted that hit-and-runs carry more lenient sentences, such as grossly negligent homicide and/or causing a traffic hazard. The most recent hit-and-run occurred in 2007, when a drunk driver ran over a police officer who had placed a spike strip on the road in Kälviä.

Gun handling errors in training settings have led to the unfortunate death of a police officer. Lessons have been learned, and the guidelines have been revised. Today, the police analyse use-of-force situations and develop their work on the basis of the results.

The anatomy of a police murder – a police officer in the field, a firearm, and an arrest

For a long time, disorder and problems occurred in public places such as at events, on trains or in parks. A clear change can be seen after the war. Threatening situations increasingly moved inside the four walls of people’s homes. Violence in close relationships has often been a reason for police visits to homes.

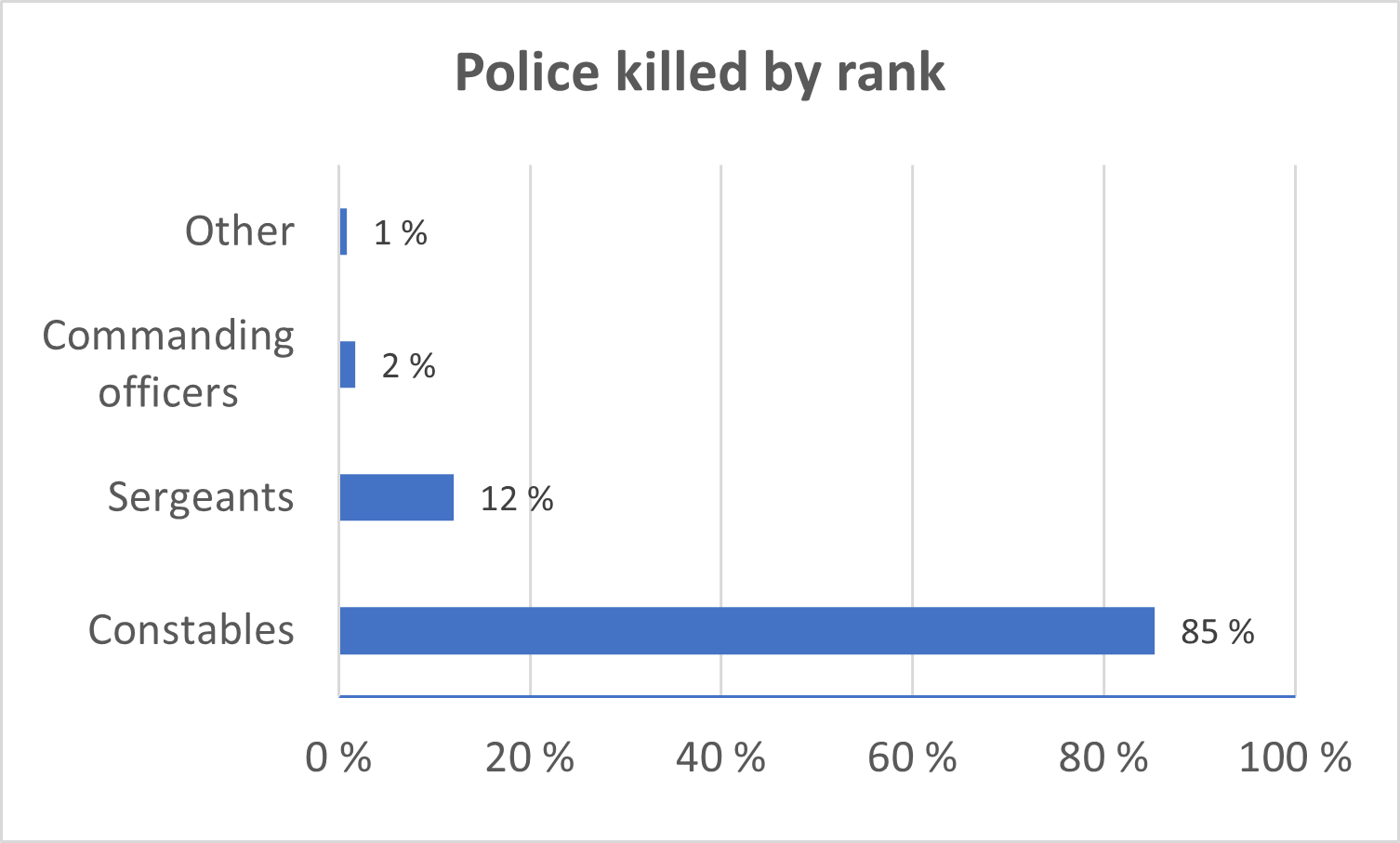

The vast majority of police fatalities – 85% – have been men, mostly uniformed officers in the field. The share of detectives from the Criminal Investigation Department, the Investigating Central Police or State Police was around 10%. All of them were men. Other police personnel, such as attendants and guards, were also among them.

Police fatalities have almost invariably occurred in the line of duty (more than 90% of cases).

Diagram: Categories of personnel killed in police fatalities

Police officers who died on the home front during the Winter and Continuation Wars have not always been classified as killed in the line of duty. Some of them were considered casualties of war, and some have ‘pro patria’ plaques. In this online exhibition, all the police officers who worked on the home front during the Winter and Continuation Wars and who were clearly on duty, on guard or carrying out official tasks are considered to have been on official duty. The executions and shootings of police officers during the Civil War were classified as acts of war.

Diagram: Data on the conditions in which police fatalities occurred

Even during their leisure time, a police officer has a duty to intervene if it is to prevent or investigate a serious crime, if there is a threat to public order, or for any other specific, equivalent reason. In 1940, Constable Eero Immonen was out walking with his family in Lappeenranta. He was confronted by a group of disorderly drunken men, whom he asked to leave the scene. One of the men fatally shot Immonen. In 1983, Sergeant Vilho Mustakangas was shot in connection with a bank robbery in Tornio. In 1994, a fight broke out in a restaurant in Järvenpää between departing customers. The restaurant’s attendant moved one of the people toward the door, and Constable Petri Henriksson went to make sure the dispute would not continue. The man shoved Henriksson, who fell and hit his head on the floor. Henriksson later died of his injuries in hospital. In 2008, a fatal accident occurred in Vihti when Sergeant Paavo Ruotsalainen, who was on his day off, was helping injured people at the scene of a road accident. The policeman was killed when he was hit by a vehicle travelling away from Helsinki.

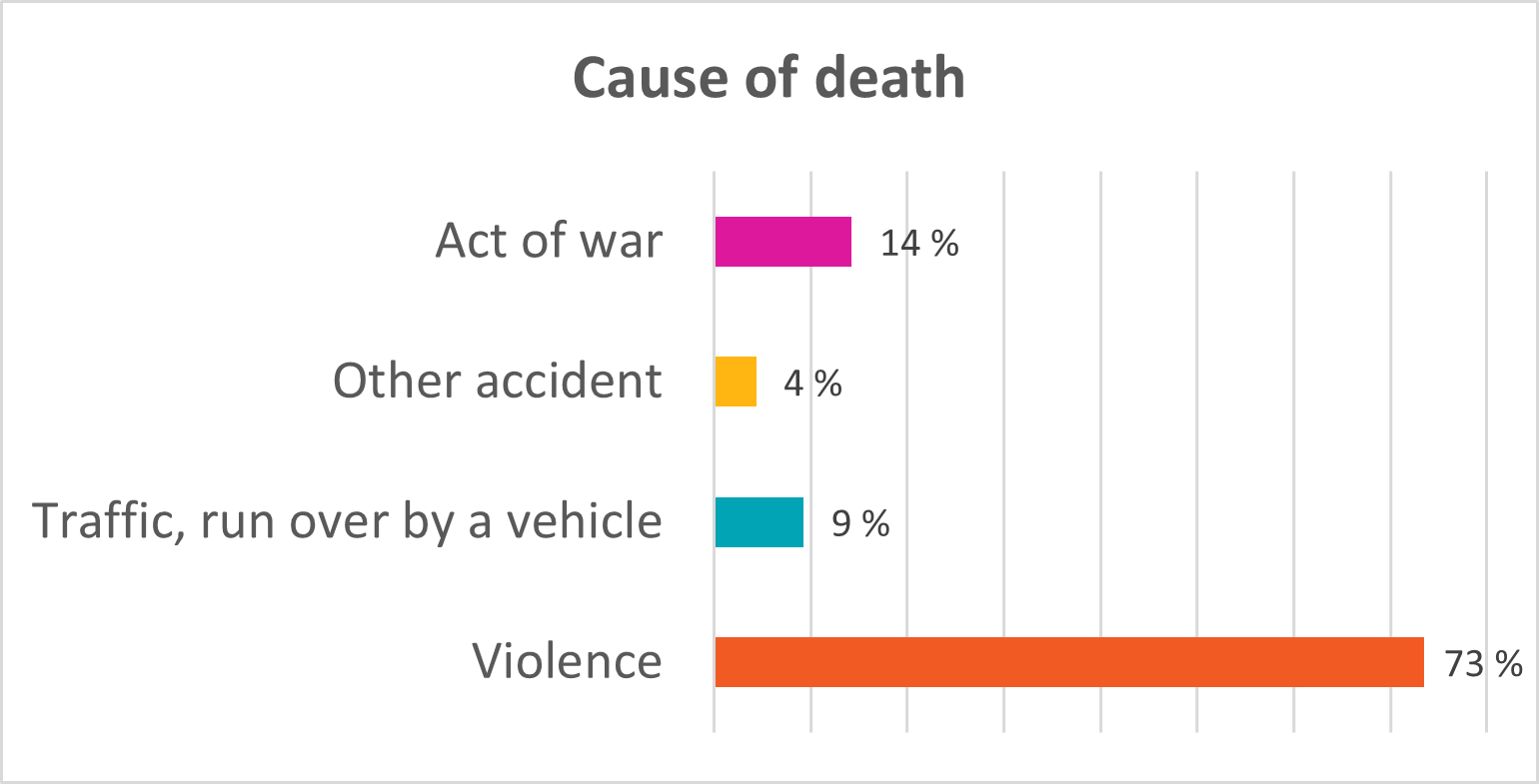

The cause of death has been classified on a case-by-case basis where sufficient information was available. The category ‘military action’ includes those who died in bombings, civil defence and during the Civil War. Constable Paul Holme of the Helsinki Police Department was killed in 1942 when he was beaten by two Soviet prisoners of war on their escape from Hanko. In this case, the cause of the police officer’s death was attributed to violence.

Diagram: Causes of death in police fatalities since Finland’s independence in 1917

How police fatalities occur

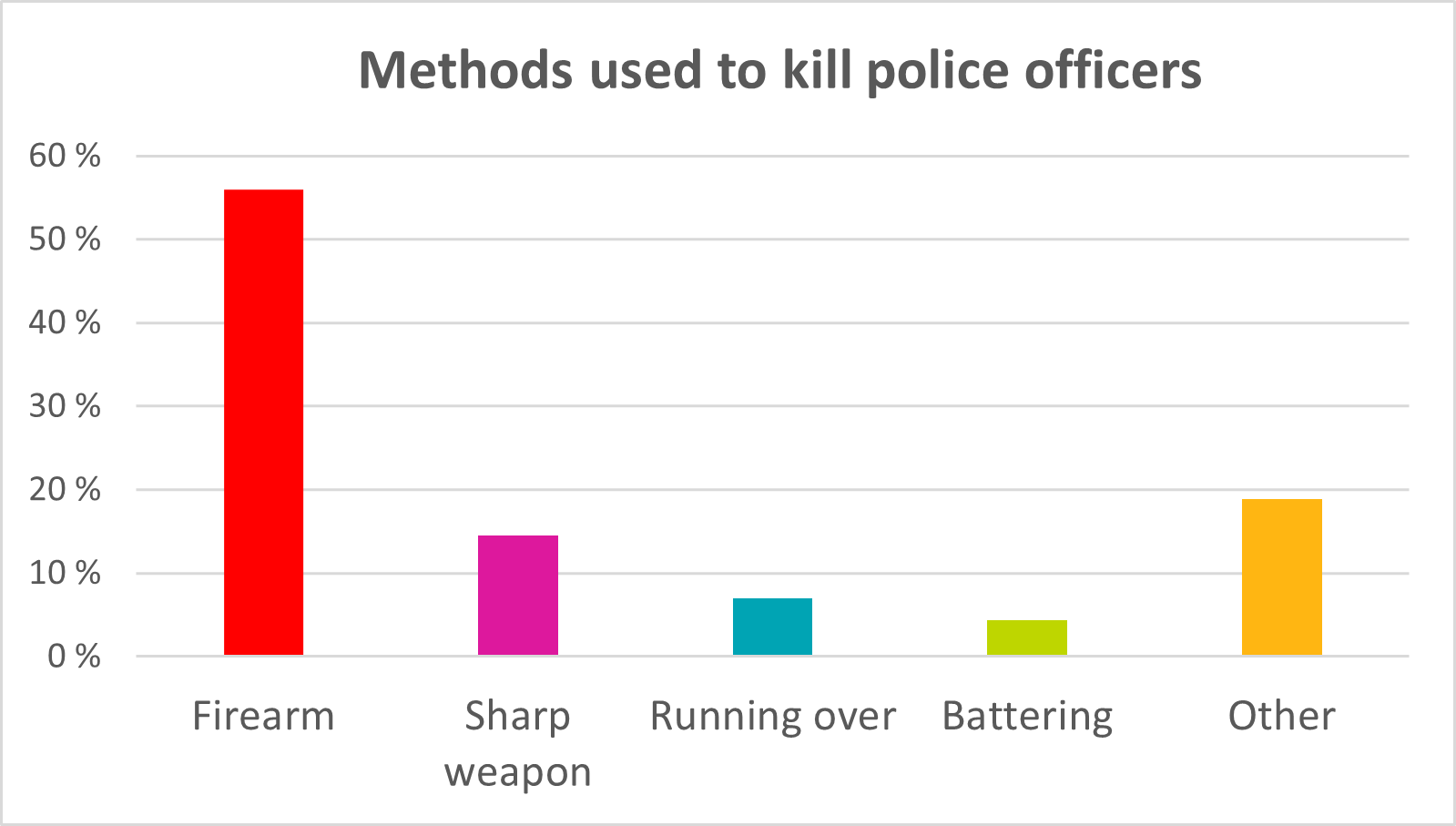

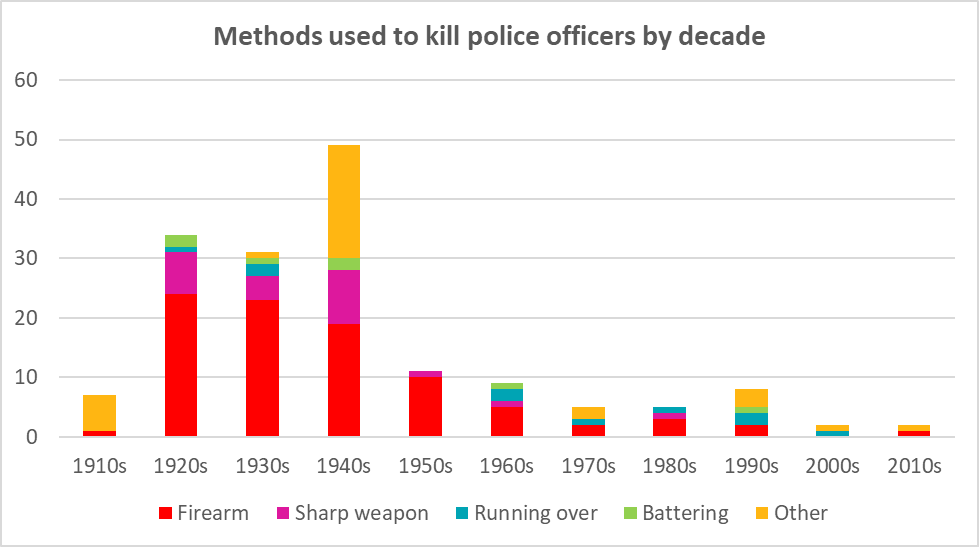

Our online database of police fatalities contains 164 police deaths. 72.5% of the police fatalities were the result of violence, corresponding to 119 police officers. 56% of police fatalities were committed by firearm. This remains the dominant cause of fatalities today. Bladed weapons account for the next highest number of deaths, at around 14%.

Especially in the early years of Finland’s independence, small arms were relatively easy to acquire, and households possessed many different types of weapons. Bladed weapons could be carried in public on a belt in the 1940s. Small in size and readily available knives are still fairly typical tools among the police’s customers. Compared with a firearm, its operating range is negligible – this explains the clear difference in the causes of fatalities.

Diagram: How police fatalities occur

The abundance of firearms in the hands of the public and the consequences of them is probably the reason why police training has emphasised firearm handling, shooting and familiarisation with firearms legislation. It should be noted, however, that until the 1990s, training was theoretical, and police officers’ firearms handling skills were not regularly monitored.

Diagram: Causes of police fatalities by decade

Although the 1940s was the darkest period for police killings in terms of numbers, the proportion of violent deaths was particularly high in the 1920s, 1930s and 1950s. 61% of police killings in the 1940s were violent deaths. In the 1930s, as many as 90% of police killings were violent. In the 1920s, violence accounted for 85% of police killings. All the police killings in the 1950s were caused by violence.

Diagram: Police officers killed by violence by decade

Fatal assaults have been relatively rare in the police and have involved various types of escape situations, where a guard or police officer has been fatally struck with various types of offensive weapons. In 1920, some people held on suspicion of being communists in the Vyborg Investigating Central Police Station escaped from their cell with the help of a hacksaw smuggled in to them. The men sawed an opening at the bottom of the cell door. At around 4 am, the duo escaped from their cell and assaulted the guard, Aleksanteri Pönkkä, with a log. In the morning, a cleaner found the guard unconscious, and he was taken to hospital, where he later died.

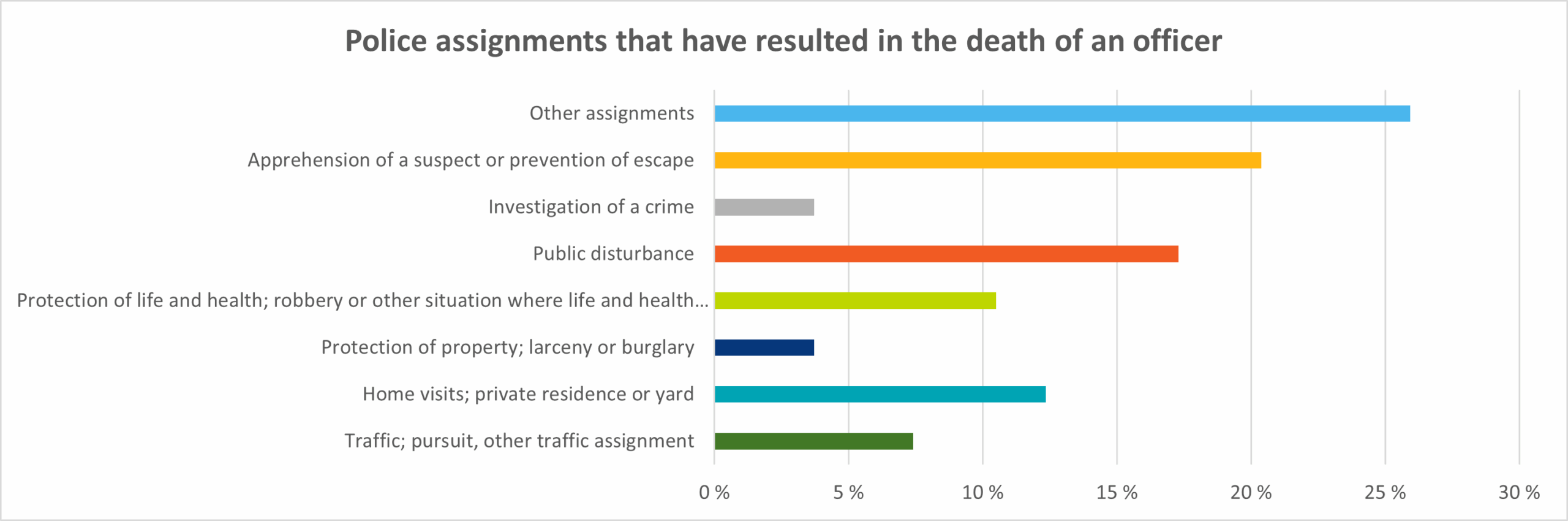

The most dangerous tasks

The most dangerous tasks for police officers have been apprehending a person or preventing an escape, disturbances in public places, and call-outs to people’s homes. Property protection tasks include, for example, the robbery of a bank or business premises, where the police have often been able to catch the perpetrators by surprise. Call-outs to people’s homes carry a higher risk because the patrol is going into an unfamiliar place where there are many possible weapons. The police’s wartime civil defence and air raid warning duties form the category of other fatalities, clearly showing that wartime was hard on the home front police force.

Most of the deceased detectives were employed by either the Investigating Central Police or State Police from the 1920s to the 1940s. Detective Frans Valmunen of the Helsinki Criminal Police was killed in 1954. Detectives Valmunen and Jaakko Pelttari went to pick up a man who had been acting in a disorderly manner. When the police arrived at the apartment, they asked his wife where he was. Suddenly, a man appeared on the scene and immediately shot at the detectives. Pelttari managed to drag himself out of the apartment and opened fire from the stairwell into the apartment. Shortly afterwards, Valmunen was able to leave the apartment. After the police surrounded the apartment, the man tried to escape from the third-floor apartment by climbing vines on the exterior wall. He fell and was taken into police custody. Detective Valmunen died in hospital.

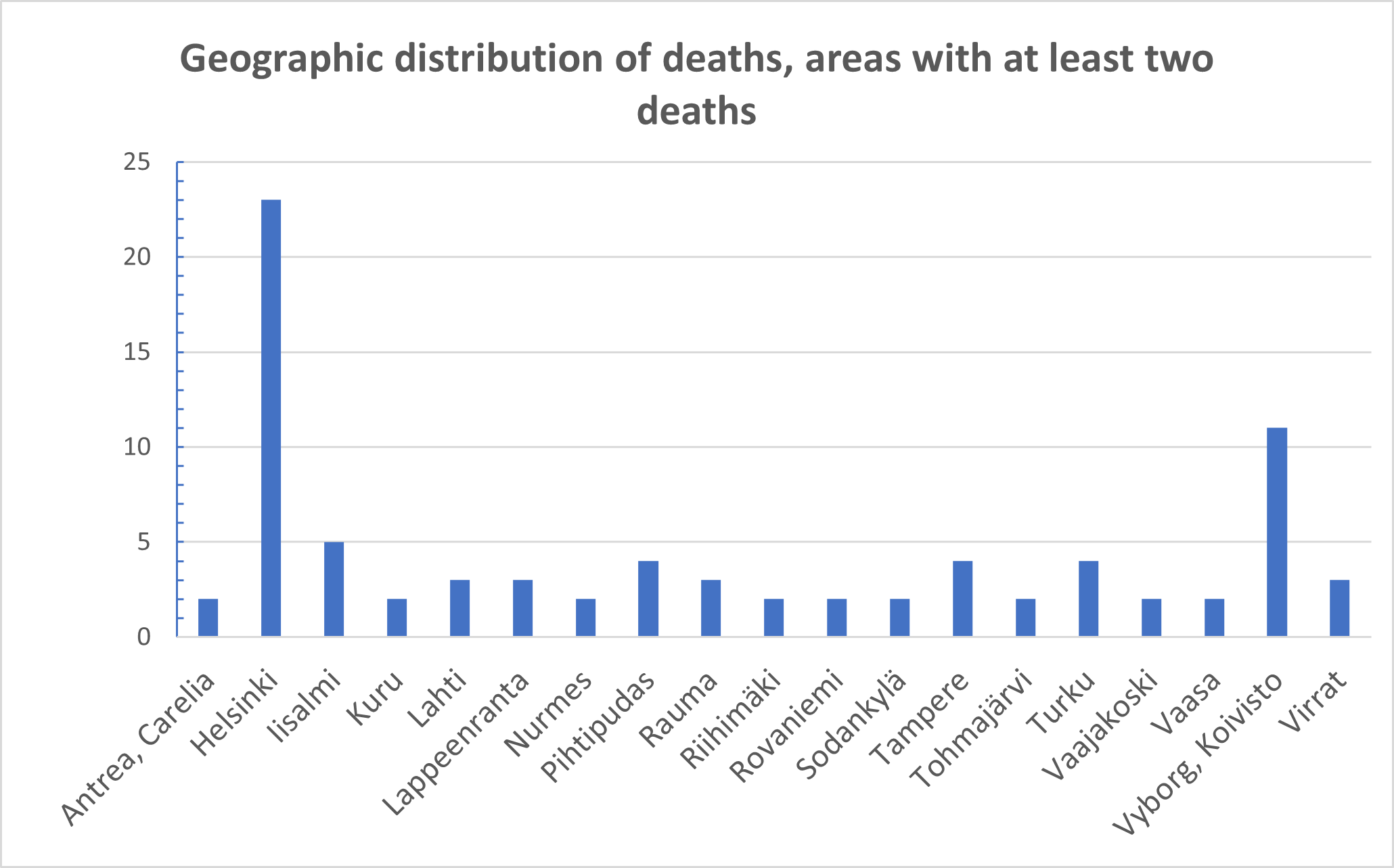

Diagram: The most dangerous types of tasks for police officers

Statistics show that police work is riskiest in the largest cities, such as Helsinki and Tampere. Until 1944, police work was especially dangerous in the Karelian region, where Vyborg was located. Specific risk factors included alcohol smuggling and the presence of illegal intelligence operatives and paratroopers in the area. Individual wartime events, such as the bombing of Iisalmi in February 1940, increased the number of police casualties in certain locations. Although the statistics indicate more police work in urban areas, violence has also occurred in rural regions. A single, exceptional event can significantly increase the number of victims in a given locality. One example of this is the number of police fatalities in Pihtipudas in 1969.

Diagram: Regional distribution of police fatalities

Police officers are always a product of their times and work according to the lessons and tactics they have been taught. As the operating environment has evolved, the police have improved and modernised their working methods.

A police educator today could certainly point to misjudgements that lead to fatalities in years gone by. In most cases, however, there was a sudden, unforeseeable variable that one might attribute to chance, fate or just plain bad luck.

Hindsight cannot bring back any of the police officers who have been lost. Equally, we should not forget the responsibility of the perpetrators: they could have chosen a different path. But they did not.