The following are two examples of incidents that had lifelong consequences and repercussions for police officers. The injuries and scars will always be present. For some, their career as a police officer was ended immediately, while others returned to work but could not do their previous jobs.

The Mikkeli explosion of 1986

Every morning, I recall the events in Mikkeli as I put on my prosthesis. Kari Tulikoura, Sergeant in the Karhu Special Intervention Unit in 1986

If I hadn’t been wearing a bulletproof vest, I wouldn’t be here telling this story. Jussi Makkula, Sergeant in the Karhu Special Intervention Unit in 1986

On 8 August 1986, at 1:30 pm, a hooded robber took 12 hostages at the Kansallis-Osake-Pankki in Jakomäki. This was an extraordinary situation for the police. No bank robber had ever taken hostages before in Finland. Bank robbers usually try to make a quick getaway from the scene of the crime.

The robber was armed with a sawn-off shotgun. He also had several kilos of dynamite. The robber demanded a car and 2.5 million Finnish markka. He refused to accept the car provided by the police because he thought it had a tracking device. He used the bank manager’s Volkswagen Passat as a getaway car, driven by a man taken hostage from among the bank’s customers. He also had two women in the car. The robber was on the back seat under a blanket.

The police followed the car across the Southern Finland. Finally, at 1 am, the car stopped at the marketplace in Mikkeli, right on the corner of the provincial government building. The situation then came to a stalemate for hours. The hijacker’s car was surrounded by a close ring of police cars. At no point did the robber negotiate with the police. Only the women in the car spoke to the police.

In the early hours of the morning, the situation escalated. The police began to close in on the car, and the hijacker threatened to blow it up. The car started moving and then stopped. At that moment, both of the female hostages managed to escape from the car. When the car started to drive away, it was interpreted as the end of negotiations. The Chief Inspector of the Karhu Special Intervention Unit gave the order for two police officers to open fire on the car. The car then exploded. It was shortly before 3:30 am.

The hijacker and his hostage, a 25-year-old man, were killed, and one of the women was injured. Several police officers were injured, including sergeants Jussi Makkula and Kari Tulikoura, who were critically injured. That day in August marked the end of 38-year-old Makkula’s career as a police officer. 41-year-old Tulikoura continued to work in the police after the incident.

Makkula, who was three metres away from the car, suffered severe head injuries. He was blinded in one eye and his right ear was torn off. His forehead was fractured, and one section of the brain responsible for storing memories was damaged. Both of his eardrums ruptured. His bicep was severed, and a large piece of his thigh muscle was torn off. The enormous pressure of the explosion tore the car to shreds, and shrapnel almost went through Makkula’s vest. Several fragments were removed from his thigh, the largest of which was eight centimetres long. The shockwave threw Tulikoura over the car, and he landed on the street. He was hit by shrapnel, his right calf muscle was ripped off his leg, and part of the bone was also detached. Efforts were made to repair it, but the leg had to be amputated fifteen centimetres below the knee. Makkula underwent dozens of surgeries; Tulikoura had about 15.

An extensive and lengthy inquiry was launched into the incident: what had actually happened and why? Who had taken the decisions, and what authority did they have? A forensic investigation indicated that the hijacker had decided to set off the explosives, and the shots had not hit him. The media was highly critical of the Karhu Special Intervention Unit and, more broadly, of the police leadership and division of responsibilities. The key question was who was in charge of the situation once it became mobile. Was the top brass in Pasila or in Mikkeli? A former police officer’s statement about a “pompous and self-confident special force full of killers” also made the headlines in the tabloids. The media also raised the question of whether the unit had acted as a team or as individual police officers.

A report by the Chancellor of Justice concluded that the police officers should not be prosecuted, although there had been errors of judgement and procedure. A further inquiry was also conducted, concluding that there had been no cover-up or improper conduct in the investigation of the case.

However, the relatives of the young man who died in the explosion brought charges against Chief Inspector Pauli Matilainen, who was in charge of the Karhu Special Intervention Unit, Sergeant Tulikoura and two other police officers. According to the relatives’ lawyer, there no doubt as to the commanding officer during the incident: it was the unit’s Chief Inspector. The lawyer said that the police’s refusal to let the car go caused the perpetrator to act in self-defence. The lawyer also claimed that the police had made errors in Mikkeli and earlier in the course of events, endangering bystanders. The legal process took seven years, ending up in the Supreme Court, where in 1993, Chief Inspector Matilainen was sentenced to unit fines for negligent homicide and negligent violation of official duty. Tulikoura and the other accused police officers were found not guilty, and the court found that they acted in self-defence. The Karhu Special Intervention Unit considered the Chief Inspector’s sentence unjust. In the words of Tulikoura: “The trial was not about seeking justice; it was about apportioning blame.”

Makkula and Tulikoura did not receive proper aftercare. They had to fight the State Treasury for years to receive compensation. The Karhu Special Intervention Unit found this difficult to accept.

A mass shooting in Hyvinkää 2012

“In more than two years, I have never been afraid of death, and I am still not. People always ask me that, and some want to know how I deal with it all. The answer is: I don’t bloody well know either! I have to thank my loved ones first and foremost. For example, my mother: she sat by my side every day; she has been the rock I can to lean on while I shed my thousands of tears. And the friends who have been here week after week to support me through the good times and the bad. How they have stood by me day after day, week after week, month after month. I am extremely grateful to my colleagues for supporting me and making me feel that I have not been forgotten. And, of course, I want to thank all those who were with me in spirit, whether they know me or not. Over the summer, I received an incredible number of cards at work, addressed to “bulletproof”. It gave me the extra strength I needed to keep going.” 21 December 2014 Bulletproof

In the morning of 26 May 2012, an 18-year-old man opened fire from the roof of a commercial building in the centre of Hyvinkää, killing two people and wounding seven others. The victims were a woman and a man, both 18 years old. Hyvinkää District Court sentenced the perpetrator to life imprisonment for two murders, seven attempted murders, and causing danger. The perpetrator was also sentenced to pay the injured parties more than €400,000 in damages and legal expenses.

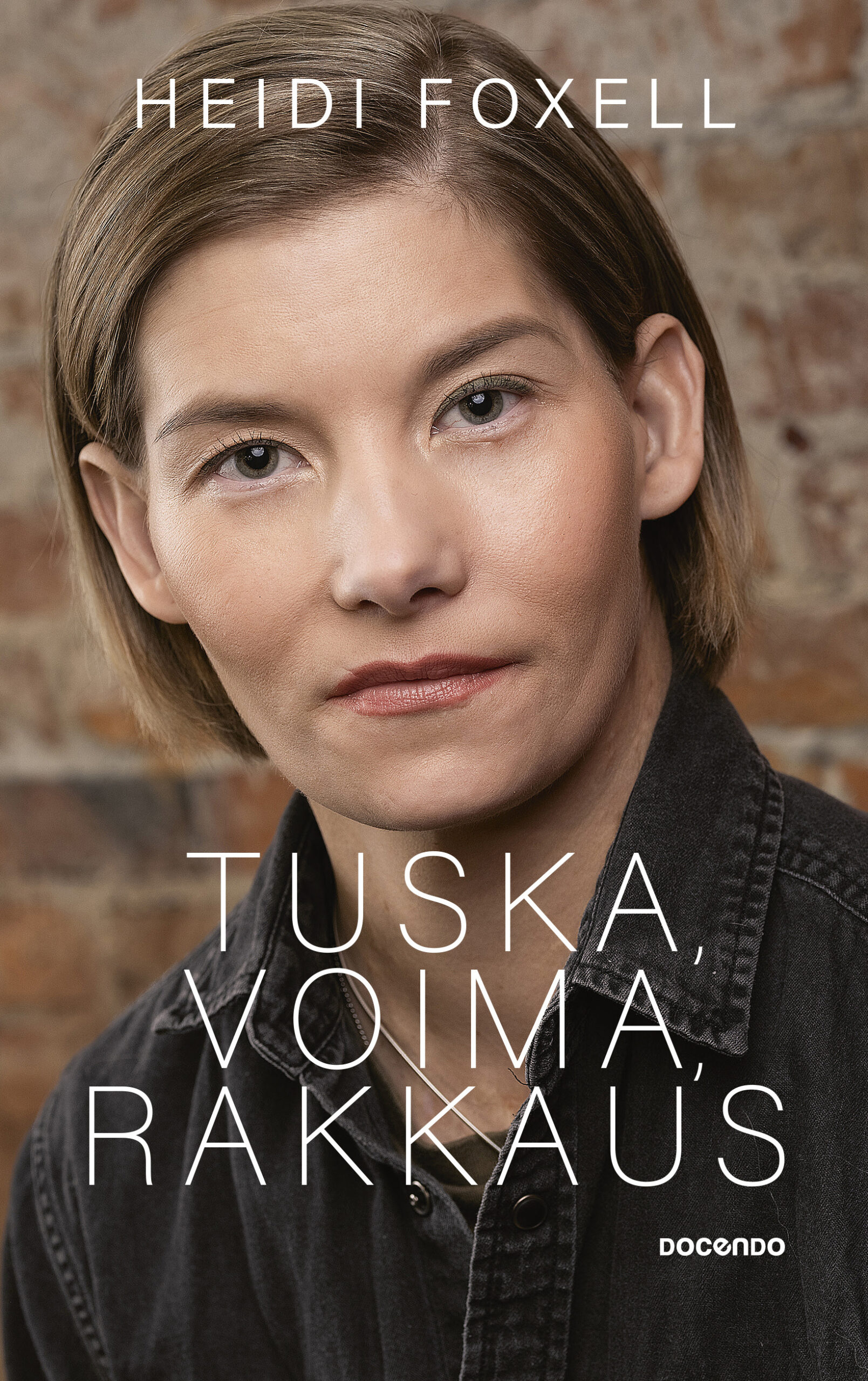

Heidi Foxell, a Constable Intern doing her practical training, was severely wounded when a shot from a deer rifle hit her in the stomach, causing major damage to her intestines. When she was brought to the emergency department, she was still able to speak, but by the time she reached the operating theatre, her condition had become critical due to blood loss. According to Ari Leppäniemi, the surgeon who treated her, the bullet entered from the upper right side of her abdomen. It ruptured the abdominal aorta, tore the duodenum, and made several holes in the rest of her small intestine. There was a severe laceration of the liver. The inferior vena cava and the right iliac vein were destroyed, and the lower part of the large intestine was completely ruptured. The bullet came to a stop in the right hip bone. Since her injury, Foxell has undergone more than 50 operations and at least as many other procedures under anaesthetic. According to Leppäniemi, this number is a world record.

Foxell first wrote an anonymous blog about her recovery under the title ‘Bulletproof’. She told of her numerous surgeries, medical errors, and more than a thousand nights spent in hospital. Foxell came to public attention when fellow police officer Tuomas Pelkonen ran a 100 km ultramarathon in her honour in August 2015.

The injury caused her to suspend her police studies, but she eventually graduated as a police officer in May 2023. The shooting left Foxell with a lifelong debilitating injury. She has toured the country speaking of the dangers of police work and the effects of indiscriminate violence, drawing on her own experiences.